Posts tagged ‘Faith’

When Your Family Becomes Your Enemy

Jesus proffers plenty of tough challenges over the course of His ministry, but one of His toughest moments comes when He warns His disciples:

Do not suppose that I have come to bring peace to the earth. I did not come to bring peace, but a sword. For I have come to turn “a man against his father, a daughter against her mother, a daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law – a man’s enemies will be the members of his own household.” (Matthew 10:34-36)

Jesus’ words here make me grimace every time I think about giving a sweet wake-up kiss to my daughter or hoisting my son up over my head as he squeals with delight. I love my family fiercely. I would guess that you do, too. Jesus’ words sound harsh. And yet, Jesus’ words are also needed. Here’s why.

Part of the background for Jesus’ teaching comes from God’s instruction to Moses:

If your very own brother, or your son or daughter, or the wife you love, or your closest friend secretly entices you, saying, “Let us go and worship other gods” (gods that neither you nor your ancestors have known, gods of the peoples around you, whether near or far, from one end of the land to the other), do not yield to them or listen to them. (Deuteronomy 13:6-8)

God loves families. But He also knows that family structures, like everything else in creation, are marked and marred by sin. Even family members can lead us astray. Some family members can lead other family members into idolatry. God’s worship, Deuteronomy 13 reminds us, must trump even our own family’s wishes.

Sometimes, then, as Jesus warns, we may fight with our families. Our own family members may, at times, feel like our enemies. We may put faith first while other family members do not. We may declare, “Jesus is Lord,” while other family members live as if they are their own lords. Such faith divisions can cause relational frictions. And yet, fighting with our family over such transcendent questions can, ultimately, prove to be fighting for our family. Because we love our family, we want our family members to experience true hope. Because we love our family, we want our family members to experience true peace. Because we love our family, we want our family members to experience God’s promise of and invitation to life. And so, even when it’s tough and even though rejection is a real possibility, we are called to carry the gospel to everyone – including our own family.

Over my years in ministry, I have had to encourage more than one parent who had a wayward child to draw boundaries and demand accountability. Yes, this would mean that a parent might have to fight with their child. But this would also mean that a parent was fighting for their child because they love their child and want what is best for their child – even if the child doesn’t want what is best for their own self.

Over the course of His ministry, Jesus was willing to make a lot of enemies. The religious leaders hated Him. The Roman government was suspicious of Him. Even one of His own disciples betrayed Him. Yet, Jesus was never afraid to speak tough truth to His enemies – not because He wanted to fight with them, but because He wanted to fight for them. Jesus loved His enemies and wanted what was best for them – even if they didn’t want what was best for their own selves.

Jesus’ words about family continue to be challenging. No one likes to fight with their family. No one wants their family members to become their enemies. But even if our family members’ response to our commitment to Christ is rejection, our response to them can be drawn from our commitment to Christ: “Love your enemies” (Matthew 5:44).

Just because someone is mad at you doesn’t mean you can’t love them. And love, after all, is what being a family is all about.

The Problem With The New York Times’ God Problem

God the Father by Cima da Conegliano, c. 1515

The polemical can sometimes become the enemy of the thoughtful. This seems to be what has happened in an opinion piece penned by Peter Atterton for The New York Times titled, “A God Problem.”

Mr. Atterton is a professor of philosophy at San Diego State University who spends his piece trotting out well-worn and, if I may be frank, tired arguments against the logical integrity of Theism. He begins with this classic:

Can God create a stone that cannot be lifted? If God can create such a stone, then He is not all powerful, since He Himself cannot lift it. On the other hand, if He cannot create a stone that cannot be lifted, then He is not all powerful, since He cannot create the unliftable stone. Either way, God is not all powerful.

This is popularly known as the “omnipotence paradox.” God either cannot create an unliftable stone or He can create an unliftable stone, but then He cannot lift it. Either way, there is something God cannot do, which, the argument goes, means His omnipotence is rendered impotent. C.S. Lewis’ classic rejoinder to this paradox remains the most cogent:

God’s omnipotence means power to do all that is intrinsically possible, not to do the intrinsically impossible. You may attribute miracles to Him, but not nonsense. This is no limit to His power. If you choose to say, ‘God can give a creature free will and at the same time withhold free will from it,’ you have not succeeded in saying anything about God: meaningless combinations of words do not suddenly acquire meaning simply because we prefix to them the two other words, ‘God can’ … Nonsense remains nonsense even when we talk it about God.

Lewis’ position is the position the Bible itself takes when speaking of God. Logically, there are some things Scripture says God cannot do – not because He lacks power, but simply because to pose even their possibility is to traffic in utter nonsense. The apostle Paul, for instance, writes, “If we are faithless, God remains faithful, for He cannot disown Himself” (2 Timothy 2:13). In other words, God cannot not be God. He also cannot create liftable unliftable stones – again, not because He lacks power, but because liftable unliftable stones aren’t about exercising power over some theoretical state of nature. They’re about the law of noncontradiction. And to try to break the law of noncontradiction doesn’t mean you have unlimited power. It just means you’re incoherent and incompetent. And God is neither. To insist that God use His power to perform senseless and silly acts so that we may be properly impressed seems to be worthy of the kind of rebuke Jesus once gave to the religious leaders who demanded from Him a powerful sign: “A wicked and adulterous generation asks for a sign” (Matthew 12:39)!

Ultimately, the omnipotence paradox strips God’s power of any purpose by demanding a brute cracking of an irrational and useless quandary. And to have power without purpose only results in disaster. For instance, uncontrolled explosions are powerful, but they are also, paradoxically, powerless, because they cannot exercise any ordered power over their chaotic power. Omnipotence requires that there is power over uncontrolled power that directs and contains it toward generative ends. This is how God’s power is classically conceived. Just look at the creation story. God’s power needs purpose to be omnipotence, which is precisely what God’s power has, and precisely what the omnipotence paradox does not care to address.

For his second objection against God, Mr. Atterton turns to the problem of evil:

Can God create a world in which evil does not exist? This does appear to be logically possible. Presumably God could have created such a world without contradiction. It evidently would be a world very different from the one we currently inhabit, but a possible world all the same. Indeed, if God is morally perfect, it is difficult to see why He wouldn’t have created such a world. So why didn’t He?

According to the Bible, God did create a world where evil did not exist. It was called Eden. And God will re-create a world where evil will not exist. It will be called the New Jerusalem. As for the evil that Adam and Eve brought into the world, this much is sure: God is more than up to the task of dealing with the evil that they, and we, have welcomed. He has conquered and is conquering it in Christ.

With this being said, a common objection remains: Why did and does God allow evil to remain in this time – in our time? Or, to take the objection back to evil’s initial entry into creation: Why would God allow for the possibility of evil by putting a tree in the center of Eden if He knew Adam and Eve were going to eat from it and bring sin into the world? This objection, however, misses the true locus of evil. The true locus of evil was not the tree. It was Adam and Eve, who wanted to usurp God’s authority. They were tempted not by a tree, but by a futile aspiration: “You can be like God, knowing good and evil” (Genesis 3:5). If Adam and Eve wouldn’t have had a tree around to use to try to usurp God’s prerogative, they almost assuredly would have tried to use something else. The tree was only an incidental means for them to indulge the evil pride they harbored in their hearts. If God wanted to create a world where evil most assuredly would never exist, then, He would have had to create a world without us.

Thus, I’m not quite sure what there’s to object to here. The story of evil’s entrance into creation doesn’t sound like the story of a feckless God who can’t get things right. It sounds like the story of a loving God who willingly sacrifices to make right the things He already knows we will get wrong even before He puts us here. God decides from eternity that we are worth His Son’s suffering.

The final objection to God leveled by Mr. Atterton has to do with God’s omniscience:

If God knows all there is to know, then He knows at least as much as we know. But if He knows what we know, then this would appear to detract from His perfection. Why?

There are some things that we know that, if they were also known to God, would automatically make Him a sinner, which of course is in contradiction with the concept of God. As the late American philosopher Michael Martin has already pointed out, if God knows all that is knowable, then God must know things that we do, like lust and envy. But one cannot know lust and envy unless one has experienced them. But to have had feelings of lust and envy is to have sinned, in which case God cannot be morally perfect.

This is the weakest of Mr. Atterton’s three objections. One can have knowledge without experience. I know about murder even though I have never taken a knife or gun to someone. God can know about lust and envy even if He has not lusted and envied. The preacher of Hebrews explains well how God can know sin and yet not commit sin as he describes Jesus’ struggles under temptation: “We do not have a high priest who is unable to empathize with our weaknesses, but we have one who has been tempted in every way, just as we are – yet He did not sin” (Hebrews 4:15). Jesus was confronted with every sinful temptation, so He knows what sin is, but He also refused to swim to sin’s siren songs. The difference, then, is not in what He knows and we know. The difference is in how He responds to what He knows and how we respond to what we know.

One additional point is in order. Though I believe Mr. Atterton’s assertion that one cannot know certain things “unless one has experienced them” is questionable, it can nevertheless be addressed on its own terms by Christianity. On the cross, Christians believe that every sin was laid upon Christ, who thereby became sin for us. In other words, Christ, on the cross, became the chief of sinners, suffering the penalty that every sinner deserved, while, in exchange, giving us the righteous life that only He could live (see 2 Corinthians 5:21). In this way, then, Christ has experienced every sin on the cross because He has borne every sin on the cross. Thus, even according to Mr. Atterton’s own rules for knowing, in Christ, God can know everything through Christ, including every sin.

I should conclude with a confession about a hunch. I am a little suspicious whether or not this 1,140-word opinion piece in The New York Times decrying faith in God as illogical was written in, ahem, good faith. This piece and its arguments feel a little too meandering and scattershot and seem a little too clickbait-y to be serious. Nevertheless, this is a piece that has gained a lot of traction and talk. I’m not sure that the traction and talk, rather than the arguments, weren’t the point.

Whatever the case, Theism has certainly seen more compelling and interesting interlocutions than this piece. God, blessedly, is still safely on His throne.

Christ, Culture, and Witness

A perennial question of Christianity asks: How should a Christian relate to and interact with broader culture? In his classic work, Christ and Culture, H. Richard Niebuhr outlines what has become the premier taxonomy of the relationship between the two as he explores five different ways that, historically, Christ and culture have corresponded:

- Christ against culture: In this view, Christianity and broader culture are incompatible and Christianity will inevitably be at odds with and should retreat from the rest of the world.

- Christ of culture: In this view, Christianity and broader culture are well suited for each other, and Jesus becomes the fulfiller of society’s hopes and dreams.

- Christ above culture: In this view, broader culture is not bad per se, but it needs to be augmented and perfected by biblical revelation and the Church, with Christ as the head.

- Christ and culture in paradox: In this view, culture is not all bad because it is, after all, created by God, but it has been corrupted by sin. Therefore, there will always be a tension between the potential of culture and its reality as well as between the brokenness of culture and the perfection of Christ.

- Christ the transformer of culture: In this view, because Christ desires to ultimately redeem culture, Christians should work to transform culture.

The categories Niebuhr outlines and the tensions he teases out in his taxonomy are just as salient today as they were when he first posed them in 1951. Indeed, they are perhaps even more so as America slides into what many have christened a “post-Christian age.”

In my view, the first two categories won’t do. To pit Christ against culture, as the first view tries to do, overlooks the fact that there is much good in culture. It can also easily lead Christians into a self-righteousness that spends so much time trying to fight culture that it forgets that Christians are part of the problem in culture, for they too are sinners.

Conversely, to team Christ with culture and to use Christ to endorse your zeitgeist of choice also will not do. As Ross Douthat explains, when this happens:

Traditional churches are supplanted by self-help gurus and spiritual-political entrepreneurs. These figures cobble together pieces of the old orthodoxies, take out the inconvenient bits and pitch them to mass audiences that want part of the old-time religion but nothing too unsettling or challenging or ascetic. The result is a nation where Protestant awakenings have given way to post-Protestant wokeness, where Reinhold Niebuhr and Fulton Sheen have ceded pulpits to Joel Osteen and Oprah Winfrey, where the prosperity gospel and Christian nationalism rule the right and a social gospel denuded of theological content rules the left.

Though I would take issue with Douthat’s characterization of Reinhold Niebuhr and Fulton Sheen as torchbearers for Christian orthodoxy, his broader point about what happens when Christ is made to mindlessly cater to culture is absolutely true. Culture, it turns out, is a much better line dancer than it is a two-stepper. It likes to dance alone and will humor Christ only as long as it needs to until it can find a way to leave Him behind and strike out on its own.

In my view, Niebuhr’s category of “Christ and culture in paradox” best explains the difficult realities of the Church’s interaction with culture and the biblical understanding of how to relate to culture. In his first letter to the Corinthians, Paul opens by writing:

When I came to you, I did not come with eloquence or human wisdom as I proclaimed to you the testimony about God. For I resolved to know nothing while I was with you except Jesus Christ and him crucified. I came to you in weakness with great fear and trembling. (1 Corinthians 2:1-3)

The Corinthians prided themselves on being enlightened and educated. Paul sardonically jibes the Corinthians for their arrogance, teasing, “We are fools for Christ, but you are so wise in Christ! We are weak, but you are strong! You are honored, we are dishonored” (1 Corinthians 4:10). To a church that prided itself in being intellectually and socially elitist, rather than engaging in rhetorical and philosophical acrobatics to impress the Corinthians when he proclaimed the gospel to them, Paul came to them with the rather unimpressive, as he put it, “foolish” message of Christ and Him crucified. Paul cut against the culture of Corinth.

And yet, at the same time he cut against the culture of Corinth, he also declared his love for broader culture and even embedded himself into broader culture in an effort to proclaim the gospel:

Though I am free and belong to no one, I have made myself a slave to everyone, to win as many as possible. To the Jews I became like a Jew, to win the Jews. To those under the law I became like one under the law (though I myself am not under the law), so as to win those under the law. To those not having the law I became like one not having the law (though I am not free from God’s law but am under Christ’s law), so as to win those not having the law. To the weak I became weak, to win the weak. I have become all things to all people so that by all possible means I might save some. (1 Corinthians 9:19-22)

Paul was not afraid to appropriate culture in service to the declaration and proclamation of the gospel so that as many people as possible might be saved.

So there you have it. Paul eschews cultural sensibilities at the same time he employs them. Because Paul knows that Christ and culture live in paradox with one another.

We would do well to follow in Paul’s footsteps. As Christians, we must not be afraid to cut against culture’s sinfulness and brokenness. But at the same time, we must also not be afraid to embrace culture’s creativity and respect its sensibilities as often as we possibly can. And we must have the wisdom to know when to do what. Otherwise, we will only wind up losing the truth to culture or losing the opportunity to share the truth with culture. And we can afford to lose neither.

Let us pray that we would faithfully keep both in 2019.

Who Needs Friends When You Have God?

A new study from the University of Michigan suggests that those who have a strong faith in God are often isolated from others. Todd Chan, a doctoral student at the university, explains:

For the socially disconnected, God may serve as a substitutive relationship that compensates for some of the purpose that human relationships would normally provide.

This is an interesting hypothesis, but studies like these do not seem to provide consistent results. W. Bradford Wilcox, the Director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia, has found that:

…religion generally fosters more happiness, greater stability, and a deeper sense of meaning in American family life, provided that family members – especially spouses – share a common faith.

In other words, contrary to what Mr. Chan found, faith in God can actually deepen and sustain relationships instead of serving as a substitute for relationships.

Certainly, there are people of deep faith who find themselves bereft of human companionship and, consequently, lonely. The Bible admits as much, while also seeking to offer comfort and a promise of companionship to those in isolated situations:

A father to the fatherless, a defender of widows, is God in His holy dwelling. God sets the lonely in families. (Psalm 68:5-6)

God does indeed promise to be there for someone when they have no one. But He doesn’t stop there. He also “sets the lonely in families.” In other words, He doesn’t just serve as a substitute for human companionship, He actually grants human companionship.

Christianity has always confessed a Triune God, in relationship with Himself from eternity, as the model for and the giver of deeper and better relationships with others. This is part of the reason why Christianity first took root in the more densely populated urban areas and why it was initially less prevalent among more rural areas. As Rodney Stark notes in his book The Triumph of Christianity:

The word pagan derives from the Latin word paganus, which originally meant “rural person,” or more colloquially “country hick.” It came to have religious meaning because after Christianity had triumphed in the cities, most of the pagans were rural people.

Christianity first flourished in cities because those were where the largest communities of people were. Christianity, it turns out, is irreducibly communal.

Jesus famously summarizes the whole of Old Testament law thusly:

“Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.” This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: “Love your neighbor as yourself.” (Matthew 22:37-39)

Jesus is clear. A relationship with God can and should lead to better relationships with others. Regardless of what Mr. Chan’s study may assert sociologically, theologically, God is not a second-string substitute for human relationships. Instead, a human, who had an intimate relationship with God and was Himself God, became our substitute on a cross so that we could have a relationship with God in spite of our sin. God is not a last resort relationship when you’re lonely, but a first love relationship who promises never to leave you alone. And there’s just no substitution for that.

The U.S. Moves Its Embassy

Credit: Daniel Majewski

This past week, a piece of legislation first passed in 1995 under President Clinton was finally implemented. The Congress at that time passed the Jerusalem Embassy Act, which recognized Jerusalem as the capital city of Israel and made plans to move the U.S. embassy to Jerusalem from Tel Aviv. Since that time, Presidents Clinton, Bush, and Obama have delayed the move, citing national security concerns. President Trump decided it was finally time to make the move. So, a week ago Monday, the new U.S. embassy opened in Jerusalem.

While celebrations were taking place at the new embassy, only miles away, along Israel’s border at the Gaza Strip, members of Hamas were protesting the move, seeking to storm the border into Israel while flying incendiary kites across the border into Israel. 50 of these rioters were killed by Israeli forces. Some other Palestinians were also killed, including an eight-month-old girl.

The antipathy between the Israelis and Palestinians is nothing new. Both groups claim rights to this region and look suspiciously at the intentions and activities of the other. The terrorist provocations of Hamas serve only to heighten tensions.

To some Christians, unalloyed support for the modern-day nation of Israel by the U.S. is a theological necessity, for they believe that anything less is a direct affront to the covenant that God made with Abraham to give him and his ancestors land in this region. Other Christians, among whom I would include myself, do not see a one-to-one correlation between the ancient theocracy of the people of Israel and the modern democracy of the nation of Israel. The true heirs of Abraham are not ethnic Jews living in a particular region of the world, but all those who, by faith, call on Abraham’s God – whether these people be ethnically Jewish or ethnically Gentile. Abraham’s true heirs do not so much concern themselves with a particular piece of land in the Middle East as they do with an all-encompassing kingdom of God.

This second view does not mean, of course, that Christians should not be concerned with the events that are unfolding in the Middle East. It is standard practice for sovereign nations to be able to name their own capitals and it is standard protocol for other nations to respect and recognize these capitals and place embassies in them, as the U.S. has now done with Israel. Geopolitically, Israel’s status as a democracy in a region that is widely known for oppressive regimes is an important and stabilizing influence. It is also essential to have a safe haven for ethnic Jews in an area of the world that has proven to be widely and often vociferously anti-Semitic.

At the same time, we cannot forget or overlook the struggle and suffering that many Palestinians face. Living under Hamas has never been easy. The small number of Christians in this region are doing yeoman’s work as they open their churches and homes to their Muslim neighbors who have been displaced by riots and bombings. They are shining examples of Christ’s love in an area of our world that is regularly marked by hate and unrest. These faithful people deserve our prayers and support. They too need safe places to live and free communities in which to thrive.

The unrest and violence that has been sparked by the move of the U.S. embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem is a reminder of the volatility in civilization’s cradle and the fragility of human life. Every U.S. president for the past 70 years has sought to broker peace in the Middle East and, sadly, every U.S. president has failed. This is because, more than a president, we need a Prince – a Prince who knows how to bring peace. He is the One in whom Israel once hoped. He is the One who Palestinian Christians now proclaim. And He is the One the whole world still needs.

Last week, a president kept a promise to move an embassy. On the Last Day, a Prince will keep His promise to bring peace. That’ll be a day to behold.

Kilauea’s Fury and God’s Promise

It’s destruction in slow motion.

It’s destruction in slow motion.

When Hawaii’s Kilauea Volcano began erupting a week and a half ago, cracks in and around the volcano began to emerge, spewing molten lava and dangerous gas. So far, 18 fissures have opened in the ground, 36 structures have been destroyed by creeping lava, and 2,000 residents have had to evacuate their homes. And geologists have no idea how long these eruptions will continue. Officials now worry that the lava lake in Kilauea’s crater will fall below the level of the groundwater, which could spark dangerous stream-driven explosions, spewing boulders – some weighing many tons – into the air.

The flow of lava is nearly impossible to stop. Its temperature checks in at around 2,000 degrees, which makes dousing it with water ineffective. Because the lava is so heavy, diversion channels also do not tend to work. The lava will simply flow over them. Residents can only stand by and watch in horror as melted, red-hot rock destroys everything it is path. David Nail, who lives on the gentle slopes of Kilauea in Leilani Estates, had his home consumed by a 20-foot tall pile of lava. “All we could do was sit there and cry,” he explained.

Natural disasters such as this raise a perennial question about faith: why, if there is a good God, would He allow such terrible disasters to happen? Christianity is unique in its approach to this question because it not only seeks to grapple with this quandary philosophically, but to empathize with people who have to endure the pain wrought by natural disasters personally.

Christianity teaches that the overall sinfulness of humanity affects and infects every part of creation. The sinfulness of humanity is why earthquakes topple communities and hurricanes flood them. The sinfulness of humanity is why severe weather strikes the south and volcanoes erupt in the west. Because of sin, creation, to borrow a memorable phrase from the apostle Paul, “has been groaning as in the pains of childbirth” (Romans 8:22). In this regard, the natural disasters we experience are anything but natural. Instead, they are a result of an alien sinfulness first thrust onto the world by our forbearers, Adam and Eve. Thus, nature doesn’t like these disasters any more than we do. Natural disasters are painful to nature, just as they are to us.

With all of this being said, Christianity also doesn’t just wag its finger ignominiously at the sinfulness in humanity for causing the suffering of humanity. Christianity teaches that God is in the midst of suffering. At the heart of Christianity is the cross – an agent not only of deep suffering, but of cruel torture. Christianity teaches that God came into suffering through His Son and endured the ultimate suffering as He bore the sins of the world in His death. Though we may not have all the answers to why God allows suffering, we do have a promise that God is deeply familiar with suffering. He suffers with us.

When Moses receives the Ten Commandments on top Mount Sinai, the scene looks downright volcanic: “The mountain…blazed with fire to the very heavens, with black clouds and deep darkness” (Deuteronomy 4:11). The Israelites at the base of the mountain who saw what was happening on the mountain, understandably, “trembled with fear” (Exodus 20:18). And yet, for all the fear Sinai’s violent eruption may have caused in the people who saw it, Deuteronomy also reminds us that “the LORD spoke…out of the fire” (Deuteronomy 4:12). Sinai may have been spewing fire and ash, but God was there, speaking His words to His people.

Kilauea is not Sinai. I highly doubt anyone will come striding down Kilauea after its eruption with a couple of stone tablets in hand. And yet, just as God was present with the Israelites camping in the shadow Sinai, God is also present with the Hawaiians living in the shadow of Kilauea. And the words that He spoke at Sinai to Israel, He still speaks to us today: “I am the LORD your God” (Exodus 20:2). God still invites us to be His people so He can love us as His children. Of this, every Hawaiian – and every person – can be assured.

The Resurrection of Jesus in History

Yesterday, Christians around the world gathered to celebrate the defining claim of their faith: the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead. The apostle Paul is very frank in his estimation of the importance of Christ’s resurrection:

If Christ has not been raised, our preaching is useless and so is your faith … And if Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile; you are still in your sins. (1 Corinthians 15:14, 17)

Paul places the full weight of Christianity’s reality and practicality on the resurrection’s actuality. If the resurrection is not a historical fact, Paul declares, then the whole of the Christian faith is foolish.

But how can we decipher whether or not the resurrection happened historically? N.T. Wright, in his seminal work, The Resurrection of the Son of God, notes that the empty tomb of Jesus combined with appearances from Jesus offers a compelling testimony to the historicity of the resurrection. If only there was only an empty tomb, Christians would not have been able to claim that Jesus rose from the dead. Likewise, if there were only phantasms of someone who looked like Jesus, Christians could not have claimed a resurrection.

Wright explains the power of this combination thusly:

An empty tomb without any meetings with Jesus would have been a distressing puzzle, but not a long-term problem. It would have proved nothing; it would have suggested nothing, except the fairly common practice of grave-robbery … Tombs were often robbed in the ancient world, adding to grief both insult and injury.[1]

Indeed, grave robbery was so common in the ancient world that emperor of Rome shortly after the time of Jesus, Claudius, issued an edict meant to intimidate anyone who would consider pillaging tombs:

Ordinance of Caesar. It is my pleasure that graves and tombs remain undisturbed in perpetuity … If any man lay information that another has either demolished them, or has in any other way extracted the buried, or has maliciously transferred them to other places in order to wrong them, or has displaced the sealing or other stones, against such a one I order … the offender be sentenced to capital punishment.[2]

Apparently, the problem of grave robbery had become so pervasive that Claudius saw no other recourse to end it than to threaten capital punishment for it. Wright consequently concludes:

Nobody in the pagan world would have interpreted an empty tomb as implying resurrection; everyone knew such a thing was out of the question.[3]

Wright continues by noting that mere appearances of Jesus alone could also not make a case for a resurrection:

‘Meetings’ with Jesus, likewise, could by themselves have been interpreted in a variety of ways. Most people in the ancient world … knew that visions and appearances of recently dead people occurred … The ancient world as well as the modern knew the difference between visions and things that happen in the ‘real’ world.[4]

It is only the combination of an empty tomb along with multiple appearances of Christ that could have given rise to the idea that Christ had, in actuality, risen from the dead. This is part of Paul’s point when he writes that Christ “appeared to more than five hundred of the brothers and sisters at the same time, most of whom are still living, though some have fallen asleep” (1 Corinthians 15:6). Paul knows that one person can suffer a delusion of a resurrection. It is much more difficult for 500 people to have the same delusion. And in case anyone has any questions about what these 500 saw, Paul notes that most of them are still living. People can simply go ask them.

With all of this being said, a primary objection to the historical veracity of the resurrection remains, which is this: dead people tend to stay that way. I have never – and I would guess that you also have never – seen a dead person come back to life. So how can we accept something as fact in the past when we cannot repeat it in the present?

Again, N.T. Wright offers two helpful thoughts. The first is that history, by its very nature, is the study of that which is unrepeatable:

History is the study, not of repeatable events as in physics and chemistry, but of unrepeatable events.[5]

In other words, just because we cannot – and, in many cases should not – repeat historical events – such as the crash of the Hindenburg, the sinking of the Titanic, or the horrors of the Holocaust – does not mean that they did not happen. To apply a standard of “repeatability” to the resurrection in order to accept its truthfulness is to apply a standard by which no other happening in history could be deemed true.

But second, and even more importantly, Wright explains that the early Christians themselves would agree that dead people stay dead! This is what makes their claim that there was a dead person who did not stay that way all the more astounding:

The fact that dead people not ordinarily rise is itself part of early Christian belief, not an objection to it. The early Christians insisted that what had happened to Jesus was precisely something new; was, indeed, the start of a whole new mode of existence, a new creation. The fact that Jesus’ resurrection was, and remains, without analogy is not an objection to the early Christian claim. It is part of the claim itself.[6]

The early Christians fully understood that what they were claiming was radically unique. But they claimed it anyway. Whatever one may think of the historicity of the resurrection, one must at least admit that the biblical witnesses saw something and experienced something that they could explain in no other way than in a bodily resurrection from death.

These considerations, of course, do not constitute an airtight or empirically verifiable case that the resurrection did, in fact, happen. But history rarely affords us such luxuries. Nevertheless, these considerations do present us with a case that makes the resurrection, according to the normal canons of history, highly probable and worthy of our consideration and, perhaps, even our embrace. There is enough evidence that we must at least ask ourselves: has Christ risen? And the answer of not only Scripture, but of history, can come back, with sobriety and credibility: Christ is risen!

Which is why, 2,000 years later, Easter is still worth celebrating.

___________________________________

[1] N.T. Wright, The Resurrection of the Son of God (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2003), 688.

[2] Ibid., 708-709.

[3] Ibid., 689.

[4] Ibid., 689, 690.

[5] Ibid., 686.

[6] Ibid., 712.

In Memoriam: Billy Graham (1918-2018)

Credit: Associated Press

Billy Graham was 99 when he entered his rest with Jesus last Wednesday. The man who was a pastor to presidents and plebeians alike leaves a legacy that is difficult to overestimate. Reverend Graham accomplished many things over his long ministry. He founded what has become the practically official periodical of evangelical Christianity, Christianity Today. He served as the president of Youth for Christ and headed the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association. He steadfastly, but also humbly, confessed a traditional, broadly orthodox Christianity, defending such doctrines as justification by faith, the sufficiency of Christ as the world’s singular Savior, the reality of heaven and hell, and the inspiration and inerrancy of Scripture. He declared these doctrines at a time when many churches, especially in the mid-twentieth-century, were drifting into modernism and began to deny these, along with many other, core tenets. But Reverend Graham will perhaps be most remembered for his moving crusades, where he preached the gospel to stadiums chocked full of eager listeners and curious onlookers. His association estimates that he preached the gospel to an estimated 215 million people in 185 countries over the course of his ministry.

I remember attending one of Billy Graham’s crusades as a child. His passion for the gospel was infectious as his preaching resonated sonorously through the stadium in which I was sitting. At the end of the evening, as he always did, he invited people to trust in Christ and come forward to receive prayer. Thousands walked down to the stage that night as strains of “Just As I Am” wafted across the hall. To say the least, it was a moving experience.

Whenever I remember my experience at this Billy Graham crusade, I am reminded of a conversation that Jesus has with Martha shortly after her brother Lazarus has died of a devastating illness. Martha, understandably, is distraught and politely registers her disappointment that Jesus was not around before her brother died to lend some help and, perhaps, a miraculous healing to him. “Lord,” Martha complains, “if You had been here, my brother would not have died” (John 11:21). Jesus, who never intended to heal Lazarus of the sickness that ailed him, but instead to raise Lazarus from the death that overtook him, responds, “I am the resurrection and the life. The one who believes in Me will live, even though they die; and whoever lives by believing in Me will never die” (John 11:25-26). These words are some of the most famous in Scripture not only because they describe what Jesus would do for Lazarus, but because they reveal who Jesus is for everyone. Jesus is the resurrection and the life. What is less famous, however, is the question that Jesus asks Martha next: “Do you believe this” (John 11:26)?

This simple question was the question behind every Billy Graham crusade. After Reverend Graham would proclaim Christ and His death for sinners, after he would declare that Christ’s resurrection can mean your resurrection, and after he would explain how Christ can bear your burdens and carry your cares, he would ask, “Do you believe this?”

When Jesus asks this question of Martha, she responds, “Yes, Lord” (John 11:27). When Reverend Graham asked it of millions, they responded with a “yes” as well.

As one who is part of the Lutheran confession of the Christian faith, I have, over the years, heard many in my tradition criticize Reverend Graham for the way in which he often spoke of faith in terms of a “decision.” His ministry even publishes a magazine titled Decision. It is certainly true that Scripture does not speak of faith as a decision of the will, but as a gift from God. The apostle Paul writes, “It is by grace you have been saved, through faith – and this is not from yourselves, it is the gift of God” (Ephesians 2:8). Unfortunately, some in my tradition have become so concerned about the possibility of implying that faith is somehow an act of the will that they refuse to invite people to faith at all. They forget to ask Jesus’ question: “Do you believe this?”

It is in this precious question of Christ that we can best come to understand and appreciate Reverend Graham’s legacy. He was never afraid to ask this question. And neither should we. Sometimes, a simple invitation, because it is a reflection of Jesus’ invitation, bears the fruit of faith. This is why this question is the question our world needs. When was the last time you asked it?

Even without a sermon, a choir, and a stadium, when you ask this question, someone might just answer, “Yes.” And all of heaven will rejoice (Luke 15:7) – including, with what I would guess might be an especially bright smile, Billy Graham.

God’s Presence in the Storm

I took the above picture two years ago when I was out for one of my early morning walks, cup of coffee in hand, along the beach of Port Aransas. Each summer, my family and I vacation in this charming Gulf town. The pictures I have seen of Port Aransas after Hurricane Harvey, along with its surrounding communities of Rockport, Aransas Pass, Port O’ Connor, Refugio, and, of course, Corpus Christi, are devastating. Homes have been flattened. Businesses have been destroyed. And now, our nation’s fourth most populous city is feeling Harvey’s wrath. Houston has been deluged by than 20 inches of rainfall. Forecasters predict that, by the time this is all said and done, some spots in Houston may receive in excess of 50 inches of rain.

None of this is easy to watch. I have called Texas home for 21 years and have many friends who live in the affected communities. To see places I know that are home to people I love be destroyed by nature’s worst is heartbreaking.

As Christians, we are never called to be idle in the face of devastation and distress. Here are a few things to consider – and to do – as this tragedy continues to unfold.

Pray

One of the many wonderful things about prayer is that it operates both as a support from God and an encouragement to others. When we cry out to God in prayer, He does hear and He does care. But prayer is important not only because of the connection it affords us with God, but because of the reassurance it can give to others. Not only praying for people, but letting people know that you’re praying for them is important in a situation like this. Pick up the phone. Send a text message. Pray for those in the Coastal Bend and Houston and then tell them you are. A note from you about your prayers for them could be just the boon their souls need in this troubled time.

Give

A couple of days ago, a friend of mine went through a disaster relief class being held by the Red Cross. He said so many people are volunteering to help victims of Harvey that the Red Cross is overwhelmed. What a great problem to have! Of course, just because lots of people are volunteering doesn’t mean there’s not lots of work still to be done and lots of resources still to be provided. You may want to consider giving to a reputable organization like the Red Cross, the Salvation Army, or the Disaster Relief Fund of the Texas District of the Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod.

Trust

In Adult Bible Class this morning at the church where I work, we were studying the story of Joseph. When Joseph is sold into slavery to the Egyptians, there is this interesting line: “The LORD was with Joseph” (Genesis 39:2). If Joseph looked only at his circumstances, it would have seemed not that the Lord was with him, but instead that the Lord had forsaken him. But we must never confuse the sweetness of our circumstances with the reality of God’s presence. The cross of Christ reveals that God’s presence is not ultimately indicated by the comforts in our lives, but by the compassion of His Son, who endured the worst of human suffering to see us through all of human suffering. Christ is there with the people of the Coastal Bend. And He is there with the people of Houston. The same Savior who was with His disciples in a storm on the Sea of Galilee and who was with the children of Israel as they passed through the waters of the Red Sea is with the Texans who are being pummeled by this storm and trying to get through some very deep waters of some very big flooding. Harvey may be catastrophic, but this storm is no match for our Savior. He will see us through.

“When you pass through the waters, I will be with you; and when you pass through the rivers, they will not sweep over you.” (Isaiah 43:2)

Herod, John the Baptist, and Sharing Our Faith

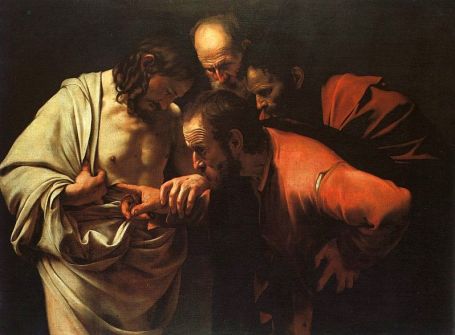

St. John the Baptist before Herod, by Mattia Pretti (1665)

In Mark 6, we are treated to a fascinating flashback. The chapter opens with Jesus teaching and then quickly turns to Him sending out His twelve disciples to preach, drive out demons, and anoint the sick. The chapter then shifts again, this time to a ruler named Herod Antipas. Herod Antipas was one of the sons of Herod the Great, the ruler who tried to kill Jesus when He was just a toddler because he considered the lad a threat to his throne. Herod Antipas, however, was not so hostile toward Jesus as he was curious about Him, especially when he heard a rumor that Jesus was “John the Baptist…raised from the dead” (Mark 6:14). Cue Mark’s flashback.

In his flashback, Mark recounts how John the Baptist died. It turns out that Herod Antipas had thrown John in prison because he had preached against Herod’s marriage to his sister-in-law, Herodias. But it was not just Herod who was upset with John. It was also his new wife, Herodias. In fact, Mark says that she “nursed a grudge against John and wanted to kill him” (Mark 6:19). And one day, she saw her opportunity. When Herod was throwing a party, Herodias’s daughter came and danced for Herod and his inebriated guests. Herod was so pleased by her performance that he offered this girl anything she wanted, including up to half his kingdom. Prompted by her mother, the girl asked Herod for John the Baptist’s head on a platter. Interestingly enough, Herod, instead of being delighted that he would finally be able to get rid of this man who had preached against his marriage, was devastated. Mark 6:26 explains that “the king was greatly distressed.” The Greek word used for “distressed” is perilupos, a word that Jesus Himself uses the night before He goes to the cross when He says to His disciples in the Garden of Gethsemane, “My soul is overwhelmed with sorrow to the point of death” (Mark 14:34). The Greek word used for “sorrow” is again perilupos. Clearly, Herod was deeply grieved, even to the point of death, by this girl’s request. But why?

As it turns out, Herod had what might be called a “love-hate relationship” with John. Mark describes their relationship like this: “Herod feared John and protected him, knowing him to be a righteous and holy man. When Herod heard John, he was greatly puzzled; yet he liked to listen to him” (Mark 6:20). The same man who threw John in prison also protected him, because he knew there was something different about him. He knew he had a righteousness and holiness that went beyond anything he had ever encountered before. Moreover, he liked to listen to John, even though he had a hard time understanding what he was talking about and, obviously, did not always heed what he said. Herod, even as he was offended by John, was also attracted to John.

Herod’s relationship with John can serve as a model for what the world’s relationship with us, as Christians, can look like. When people watch you, do they see a righteousness and a holiness beyond anything they have ever encountered before because, instead of your righteousness and holiness being merely meritocratic, it is Christocentric? And when you speak about your faith to others, even if they are puzzled by what you have to say, do you leave them wanting to hear more?

Just as Herodias hated John, there will be some who hate us simply because we are Christians. But there will also be others who are intrigued by us. May we never forget to engage these people, model Christ for these people, and speak the gospel to these people. For what they are puzzled by today may just be the very thing they believe in tomorrow.