Posts tagged ‘Love’

Mr. Zuckerberg Goes To Washington

Credit: NBC News

Last week, Mark Zuckerberg found himself in the hot seat as he faced Congress, who, as The New York Times reports, turned their interview with him into:

…something of a pointed gripe session, with both Democratic and Republican senators attacking Facebook for failing to protect users’ data and stop Russian election interference, and raising questions about whether Facebook should be more heavily regulated.

Along with broad calls for heavier regulations for the sake of people’s privacy came concerns that Facebook might also regulate people’s posts, especially in light of the many contested “fake news” posts that circulated during the 2016 presidential election on social media. Senator Ben Sasse of Nebraska highlighted this concern, telling Mr. Zuckerberg:

Facebook may decide it needs to police a whole bunch of speech that I think America may be better off not having policed by one company that has a really big and powerful platform … Adults need to engage in vigorous debates.

At issue for Senator Sasse is whether or not a corporation like Facebook will be able to responsibly regulate all kinds of posts that, regardless of their intellectual and logical quality, are politically, though not necessarily corporately, protected under the First Amendment. Senator Sasse is concerned that Facebook may simply begin regulating speech with which Facebook management does not agree. The senator offered the example the abortion debate as a potential flashpoint if social media speech regulations were to be instituted:

There are some really passionately held views about the abortion issue on this panel today. Can you imagine a world where you might decide that pro-lifers are prohibited from speaking about their abortion view on your platform?

Mr. Zuckerberg responded that he “certainly would not want that to be the case.”

Corporate regulation of speech is indeed a concern, for even the best regulatory intentions often come with unintended – and sometimes awful – consequences. At the same time, for Christians, a devotion to free speech must never become an excuse for reckless speech, for reckless speech can be dangerously damaging. As Jesus’ brother, James, reminds us:

The tongue is a small part of the body, but it makes great boasts. Consider what a great forest is set on fire by a small spark. The tongue also is a fire, a world of evil among the parts of the body. It corrupts the whole body, sets the whole course of one’s life on fire, and is itself set on fire by hell. (James 3:5-6)

Thus, with this in mind, it is worth it to reflect for a moment on how we exercise our tongues – on social media, and in all circumstances. In our speech – and in our posts – Scripture calls us to two things.

First, we must love the truth.

When the apostle Paul writes to a pastor named Timothy, he exhorts him:

What you heard from me, keep as the pattern of sound teaching, with faith and love in Christ Jesus. Guard the good deposit that was entrusted to you – guard it with the help of the Holy Spirit who lives in us. (2 Timothy 1:13-14)

The Greek verb that Paul uses for “guard” is philasso, from which we get the English word “philosophy.” “Philosophy” is a word that, etymologically, translates as “love of truth.” As Christians, we are called to love the truth. We do this by expecting the truth from ourselves, by defending the truth when we see lies, and by seeking the truth so we are not duped by deceit. In the sometimes wild world of social media, do we tell the truth about ourselves, or do we paint an intentionally deceptive portrait of ourselves with carefully curated posts? Do we defend the truth when we see others being defamed, or do we pile on because we find certain insults humorous? Do we seek the truth before we post, or do we pass on what we read indiscriminately because it fits our preconceived biases? As people who follow the One who calls Himself “the truth,” we must love the truth.

Second, we must speak with grace.

Not only is what we say important, how we say it is important as well. The apostle Paul explains it like this: “Let your conversation be always full of grace, seasoned with salt, so that you may know how to answer everyone” (Colossians 4:6). There are times when communicating the truth can be difficult. But even in these times, we must be careful to apply the truth as a scalpel and not swing it as a club. The truth is best used when it cuts for the sake of healing instead of when it bludgeons for the thrill of winning. This is what it means to speak the truth with grace. Paul is clear that he wants the truth proclaimed “clearly” (Colossians 4:4), but part of being clear is being careful. When anger, hyperbole, and self-righteousness become hallmarks of “telling it like it is,” we can be sure that we are no longer actually “telling it like it is.” Instead, we are obfuscating the truth under a layer of vitriol and rash rants.

Facebook has a lot to answer for as investigations into its handling of people’s privacy continue. It appears as though the company may not have been completely forthcoming in how it operates. And their deceit in this regard is getting them into trouble. Let’s make sure we don’t fall into the same trap. Let’s be people of the truth – on social media and everywhere.

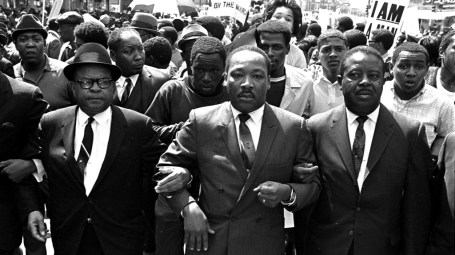

The Legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

1968 was a watershed year in American history. It was in 1968 that North Vietnam launched the Tet Offensive against South Vietnam and its ally, the United States. It was in 1968 that two U.S. Athletes stared downward at the Olympic Games in Mexico City, hands stretched upward, after winning the bronze and gold medals in the 200-meter sprint, to protest racial inequities. It was in 1968 that 11 million workers in Paris – more than 22 percent of France’s total population – went on strike, with riots erupting that were so violent, they forced the French president, Charles de Gaulle, to flee the country for a short time. It was in 1968 that the leading Democratic candidate for president, Robert F. Kennedy, was assassinated at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. And it was in 1968, on April 4 – 50 years ago this past week – that the venerable icon of the civil rights movement, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., was assassinated while standing outside his room at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis.

To this day, American society is still seeking to come to terms with Dr. King’s death and the horrific racism that sparked it. Debates over how, how deeply, and whether large swaths of America are racist rage, with no end in sight. In a decade that was rife with segregation, Dr. King was a powerful and prolific voice for racial reconciliation and human dignity. This is why 50 years after his death, we still need his wisdom and vision.

Dr. King drew from the rich well of the biblical prophets’ cries for justice to paint a portrait of what could be. From the dream that he so vividly described on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in 1963 to the melancholy and pointed letter that he wrote to Christian clergymen while in a Birmingham jail earlier that same year, Dr. King knew that racism was a sin that could – and must – be overcome. As he explained when he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964:

I refuse to accept despair as the final response to the ambiguities of history. I refuse to accept the idea that the “isness” of man’s present nature makes him morally incapable of reaching up for the eternal “oughtness” that forever confronts him … I refuse to accept the view that mankind is so tragically bound to the starless midnight of racism and war that the bright daybreak of peace and brotherhood can never become a reality …

I believe that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word in reality. This is why right temporarily defeated is stronger than evil triumphant … I still believe that one day mankind will bow before the altars of God and be crowned triumphant over war and bloodshed, and nonviolent redemptive good will proclaim the rule of the land. “And the lion and the lamb shall lie down together and every man shall sit under his own vine and fig tree and none shall be afraid.” I still believe that we shall overcome!

Dr. King’s fight against racism was tireless, and his optimism that racism would one day be overcome by brotherhood was indefatigable, for it was rooted in a hope in a God who creates all men equal. Dr. King unwaveringly believed that God’s creative design of dignity could conquer even the acridest apartheid of men.

As Christians, we must never forget that racism cuts against the very heart of the gospel itself. Racism exchanges the love of all for the hate of some and forgets that the very people it hates were loved by Christ so much that He died for them. To be a racist is to make a mockery out of the very love of God. In this way, racism is not only an ugly blight societally, but an extremely dangerous gamble spiritually, for God will not be mocked.

Dr. King was hated by many. But those who hated him, he declared:

I have … decided to stick with love, for I know that love is ultimately the only answer to mankind’s problems. And I’m going to talk about it everywhere I go. I know it isn’t popular to talk about it in some circles today. And I’m not talking about emotional bosh when I talk about love; I’m talking about a strong, demanding love. For I have seen too much hate. I’ve seen too much hate on the faces of sheriffs in the South. I’ve seen hate on the faces of too many Klansmen and too many White Citizens Councilors in the South to want to hate, myself, because every time I see it, I know that it does something to their faces and their personalities, and I say to myself that hate is too great a burden to bear. I have decided to love.

Jesus decided to love – and He redeemed mankind. If love has this kind of power, there is simply no better thing to choose.

ISIS and Sufis

Credit: Akhtar Soomro / Reuters

Because it was over the long Thanksgiving weekend, the ISIS attack on an Egyptian Sufi mosque that killed 305 people a week ago Friday received some attention, but not as much as it might have normally. But it is important. The sheer scope of the tragedy is gut-wrenching. The mass shooting at the Mandalay Bay in Las Vegas claimed 59 lives. The mass shooting at the First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs claimed 26. The attack on this mosque killed over 300. It is sobering to try to fathom.

Part of what makes this attack so disturbing is that one group of Muslims – or at least self-identified Muslims – in ISIS perpetrated this attack against another group of Muslims who are Sufi. At its heart, this attack was driven not by political or cultural differences, but by an all-out holy war. Rukmini Callimachi, in a report for The New York Times, explains:

After every attack of this nature, observers are perplexed at how a group claiming to be Islamic could kill members of its own faith. But the voluminous writings published by Islamic State and Qaeda media branches, as well as the writings of hard-liners from the Salafi sect and the Wahhabi school, make clear that these fundamentalists do not consider Sufis to be Muslims at all.

Their particular animus toward the Sufi practice involves the tradition of visiting the graves of holy figures. The act of praying to saints and worshiping at their tombs is an example of what extremists refer to as “shirk,” or polytheism.

Certainly, the veneration of the dead is a problem – not only for many Islamic systems of theology, but for orthodox Christianity as well. When the Israelites are preparing to enter the Promised Land, God warns them:

Let no one be found among you who sacrifices their son or daughter in the fire, who practices divination or sorcery, interprets omens, engages in witchcraft, or casts spells, or who is a medium or spiritist or who consults the dead. Anyone who does these things is detestable to the LORD; because of these same detestable practices the LORD your God will drive out those nations before you. (Deuteronomy 18:10-12)

On this, many Christians and Muslims agree: venerating the dead is not only superstitious and paganistic, it smacks of polytheism by exalting a departed soul to the position of God, or, at minimum, to a position that is god-like. Yet, one can decry the veneration of the dead without creating more dead, an understanding that many others in the Muslim world, apart from ISIS, seem to be able to maintain with ease. Theological disagreements can be occasions for robust debate, but they must never be made into excuses for bloodshed.

There are some in the Christian world, who, like Sufi Muslims, venerate those who are dead in ways that make other Christians very uncomfortable. Catholicism’s veneration of the saints, for instance, is rejected as unbiblical and spiritually dangerous by many Protestants, including me. But this does not mean that there are not many theological commitments that I don’t joyfully share with my Catholic brothers and sisters, including a creedal affirmation of Trinitarian theology as encapsulated in the ecumenical creeds of the Church. I may disagree with Catholics on many important points of doctrine, but they are still my friends in Christ whom I love.

Jesus famously challenged His hearers to “love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you” (Matthew 5:44). Part of what I find so compelling about Jesus’ challenge is not just its difficulty – though it is indeed very demanding to try to love someone who hates you – but its keen insight into the devastating consequences of hate. If you love your enemy, even when it’s difficult, you can most certainly love your friends, and, by God’s grace, you may even be able to make friends out of enemies when they become overwhelmed by your love. But if you hate your enemy, even your friends will eventually become your enemies, and you will hate them too. Why? Because hate inevitably begets more hate.

ISIS has made a theological system out of hate. Thus, they have no friends left to love. They only have enemies to kill, including other Muslims. Christians, however, worship a God who not only has love, but is love (1 John 4:16). For all the Sufis who are mourning, then, we offer not only our condolences, but our hearts, and we hold out the hope of the One who is not only the true God, but the one Savior, and who makes this promise: ISIS’s hate that leads to death is no match for Jesus’ love and His gift of life.

Killing Racism: When Self-Preservation Meets Self-Sacrifice

Credit: Getty Images

President Trump, in the least controversial of his three statements on this tragedy, declared:

Racism is evil. And those who cause violence in its name are criminals and thugs, including the KKK, neo Nazis, white supremacists, and other hate groups that are repugnant to everything we hold dear as Americans. We are a nation founded on the truth that all of us are created equal. We are equal in the eyes of our Creator. We are equal under the law. And we are equal under our Constitution. Those who spread violence in the name of bigotry strike at the very core of America.

As Christians, we can agree that “racism is evil.” But it is evil not just because, as the president noted, it is an affront to the dignity that is inherently ours by virtue of the fact that we are created by Almighty God; it is evil also because it is fundamentally antithetical to the Christian gospel. One of the hallmarks of the gospel of Christ is its power to reconcile us not only to God in spite of our sin, but with each other in spite of our differences. The apostle Paul explains:

Remember that formerly you who are Gentiles…were separate from Christ, excluded from citizenship in Israel and foreigners to the covenants of the promise, without hope and without God in the world. But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far away have been brought near by the blood of Christ. For He Himself is our peace, who has made the two groups one and has destroyed the barrier, the dividing wall of hostility … Consequently, you are no longer foreigners and strangers, but fellow citizens with God’s people and also members of His household. (Ephesians 2:11-14, 19)

Paul here identifies two groups of people – Jews and Gentiles – and says that, in Christ, the things that once separated them have now been destroyed. The faith they share trumps any racial and cultural differences they might have.

This theme of different groups being brought together in Christ is not unique to Paul. This is the centerpiece of the day of Pentecost where “Parthians, Medes and Elamites; residents of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the parts of Libya near Cyrene; visitors from Rome (both Jews and converts to Judaism); Cretans and Arabs” (Acts 2:9-11) all hear the gospel declared to them in their own languages. This is also the centerpiece of eternity itself, as people “from every nation, tribe, people and language” (Revelation 7:9) come together in worship of the Lamb of God. It turns out that it is awfully hard to have a Christian view of and hope for heaven while espousing racism, for, in eternity, all people of all races will be glorified as precious and redeemed in God’s sight. Heaven has no room for racial divisions.

With all this being said, we must now ask ourselves: how do we fight the racism that continues to plague our society? Perhaps the best way to fight it is to strike at its root. And although there is no singular root, I agree with Ben Shapiro when he argues that identity politics is one of the primary causes of many of our modern-day manifestations of racism. Although identity politics is classically associated with the political left, Shapiro notes that groups like “Unite the Right” engage in “a reactionary, racist, identity-politics…dedicated to the proposition that white people are innate victims of the social-justice class and therefore must regain political power through race-group solidarity.” In other words, it is the drive for self-preservation that fuels much of the racism we see today.

In order to confront our modern-day manifestations of racism, we must take our tendency toward self-preservation and exchange it for something else – something better – like the beauty of self-sacrifice. Thankfully, the call to self-sacrifice is one that Christianity is perfectly poised to make, for we follow a Savior who sacrificed Himself for our salvation and who reminds His disciples that “whoever wants to save their life will lose it” (Mark 8:35). Jesus calls us to lives of self-sacrifice.

What does self-sacrifice look like practically? The Declaration of Independence famously claims that “all men are created equal.” But in order to truly adopt this claim as our own, we must clarify what is meant by “all men.” In many people’s experience, “all men” includes two groups: “us men,” meaning those who are like us and share our background and beliefs, and “those men,” meaning those are unlike us and conflict with our background and beliefs. Human nature tends to prioritize “us men” over “those men.” In other words, even if we believe, in principle, that “all men are created equal,” we tend to concern ourselves with those who are like us – “us men” – before we stop to consider the needs of those who are unlike us – “those men.” Christianity calls us to flip this order and first consider “those men” before we attend to the concerns of “us men.” The apostle Paul makes this point when he writes, “In humility value others above yourselves, not looking to your own interests but each of you to the interests of the others” (Philippians 2:3-4). This, it should be noted, is precisely how Christ lived. For Him, every man belonged to the category of “those men,” for He alone stood as the God-man. No one was like Him. And yet, rather than preserving Himself, He sacrificed Himself for us. Christ is the very essence of self-sacrifice.

Last week, I came across an article written several years ago by Bradley Birzer, a professor of history who holds the Russell Amos Kirk Chair in American Studies at Hillsdale College. In his article, Professor Birzer tells the story of a priest named Maximilian Kolbe. The story is so poignant and compelling that it is worth quoting at length:

St. Maximilian Kolbe, a Roman Catholic priest, had been taken prisoner by the Nazis, as had been vast number of his fellow men, Poles, Jews, Catholics, and Lutherans. The Nazis seemed to avoid discrimination when it came to state sanctioned murder.

On the last day of July 1941, a prisoner had attempted to escape the terror camp. As punishment, the commandant called out ten random names – the names of those to be executed in retribution for the one man trying to escape. One of the names called had belonged (or, rather, had been forced upon) a husband and father. As the man pleaded his case, Father Kolbe came forward and offered his life for the one pleading. The commandant, probably rather shocked, agreed, and Kolbe, with nine others, stripped naked, entered the three-foot high concrete bunker. Deprived of food, water, light, and toilets, the men survived – unbelievably – for two weeks. Madness and cannibalism never overcame them, as the Nazis had hoped. Instead, through Kolbe’s witness as priest and preacher and as an incarnate soul made in the image of Christ, grace pervaded the room. When the commandant had the room searched two weeks later, only to find the men and Father Kolbe alive, he furiously ordered them all to be injected with carbolic acid.

The man who removed Kolbe’s body offered a wondrous testimony under oath. Kolbe, he said, had been in a state of definite ecstasy, his eyes focused on something far beyond the bunker, his arm outstretched, ready to accept the death of the chemicals to be injected in him.

Father Kolbe lived a life of self-sacrifice, even when a life of self-sacrifice meant offering himself unto death. As he awaited his fate, he preached the gospel, which burnished in his bunker-mates love for each other instead of competition against each other over the meager resources of the Nazis’ concentration camp. And because of Father Kolbe’s willingness to sacrifice himself, Poles, Jews, Catholics, and Lutherans were able to stand together.

Do you want to confront racism? Just live like that. It is difficult to be racist when you put others before yourself, because instead of being suspicious of others, you learn to love others. And love and racism simply cannot coexist. In fact, love, when it is embodied in self-sacrifice, not only confronts racism, it kills it. And it’s much better to kill an evil like racism than to kill a person like in Charlottesville.

When Not Practicing What You Preach About Sex Is a Good Thing

It’s no secret that we live in a sexually infatuated society. In an article for The Federalist, Shane Morris cites research showing that 92 percent of the 174 songs that made it into the Billboard Top 10 during 2009 included references to sex. What’s more, in another study, researchers found that from the 1960s to the 2000s, songs with sexual subject matter sung by male artists went from 7 percent in the decade known for its “make love, not war” attitude to a whopping 40 percent in the 2000s. In another compelling factoid, Morris mentions that out of Billboard’s top 50 love songs of all time, only six are from the year 2000 or later. Why? Because artists just don’t sing about love like they used to. Instead, they boast about sex.

And yet…

For all our boasting about sex, it turns out that actual sexual intimacy between real human beings is down. In a study published in the Archives of Sexual Behavior, researchers found that “American adults had sex about nine fewer times per year in the early 2010s compared to the late 1990s” due primarily to “an increasing number of individuals without a steady or marital partner.” Even those who are married reported “a decline in sexual frequency among those partners.” Interestingly enough, these same researchers found that, out of all the recent generations, it was the generation born in the 1930s that enjoyed intimacy most often.

As Christians, we know that part of our culture’s quandary over what we say and what we actually do about sex comes because sex has become largely decoupled from its biblical context – that of marriage. Our culture’s vaulted sexual revolution has not led to more or better sex. It’s just led to the enshrinement of sex as an idol. And anything that is idolized inevitably becomes counted on for too much, which, in turn, makes it deliver less than it could if it was kept in its proper place in the first place. Thus, it is no surprise that our near-worship of sex has not led to an increase in sex.

There are some hopeful signs that we, as a society, know, even if only intuitively, that we have taken a wrong turn when it comes to sex. In a post for National Review, Max Bloom notes that for all of the avant-garde attitudes Millennials might have about sex, in their actual intimate lives, they are trending toward the traditional:

Millennials are more than twice as likely to have had no sexual partners in their early 20s than those born in the 1960s. In general, Millennials have about as many sexual partners as Baby Boomers and considerably less than Generation X-ers – those born in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s.

It turns out that, when it comes to sexual partners and practices, what is old is new again. There is still plenty of room for monogamy and abstinence. Bloom notes that Millennials are trending traditional in other ways, too: “They are less likely to drink, smoke marijuana, or use cocaine than previous generations.” But for all their traditional habits, one non-traditional trend continues: Millennials continue to increasingly drift from traditional religious practices such as worship and prayer.

So, what does all this tell us? First, it tells us that even as our culture drifts from any understanding of or appreciation for Christian orthodoxy, natural law, à la Romans 2:14-15, seems to still hold some sway over our concrete propriety. Second, our trending sexual traditionalism also tells us that our God really does have, even for a society that can be as misguided as ours can be, what the Calvinists call “common grace.” Regardless of whether or not our culture believes in traditional sexual mores, the very fact that so many of us live by a more traditional code of ethics that protects us from the pain, fear, and heartbreak that sexual egalitarianism inevitably brings is a testament to God’s broad, gracious protection of society. To those who have walked down the road of sexual anarchy and have had their hearts and bodies broken in the process, Christians must be prepared to offer love, understanding, guidance, and grace.

Hopefully, the materializing rupture between what we as a culture believe and what we as a culture do when it comes to sex will lead us to try to reconcile our curious pockets of orthopraxy with a much-needed orthodoxy. Our culture will be better for it. And who knows? We might just be able to stop boasting about sex in songs because we’ll actually be enjoying more love in life.

When Politics Leads to Bloodshed

Credit: Shawn Thew / EPA

When 66-year old James Hodgkinson opened fire on a ball field in Alexandria, Virginia this past Wednesday, he seemed to be targeting Republican members of Congress, who were engaged in a friendly game of baseball. Shortly before the shooting, the suspect asked two representatives if the congressional members playing that day were Republicans or Democrats. When they responded that they were Republicans, he left. But when he returned, he came toting a rifle, which he used to wound four people, including the majority whip for the House of Representatives, Steve Scalise, who sustained severe injuries. He remains in critical condition at an area hospital.

Following the shooting, investigators sprang into action and quickly discovered that Hodgkinson had a sharp disdain for Republicans, posting many virulently anti-Republican messages on social media.

This is where we are. Our nation has become so bifurcated politically that a difference in party can become a motive for attempted murder.

In general, recent times have not proven to be good ones for political discourse in our country. From a magazine cover depicting a comedian holding a severed, bloodied head bearing a curious resemblance to the president’s head, to a modernized telling of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar in a New York park that portrays the assassination of someone who, again, appears strikingly similar to the president, to the president himself joking during his campaign that he could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue in New York and shoot someone and his voters would still support him, political discourse has, to put it mildly, taken a nosedive.

So often, such reckless political flame-throwing is defended on the grounds of the blessed freedom of speech that we enjoy in our country. “If we can say it, we will say it,” the thinking goes. Indeed, no matter what political views you may hold, it is likely that some in your political camp have said things about opposing political factions that, though they might be legal according to the standards of free speech, are certainly not moral according to the guidances of God’s good Word. Free speech does not always equate to appropriate speech. Perhaps we should ask ourselves not only, “Can I say this?” but, “Should I say this?”

Part of the problem with our political discourse is that so often, so many seem to be so content with ridiculing the other side that they forget to offer cogent arguments for the benefits of their side. But when we define ourselves by how we belittle our opponent, we turn our opponents into nothing short of evil monsters. We stop disagreeing with them and begin hating them. And our political discourse turns toxic.

President John F. Kennedy, shortly after the Cuban Missile Crisis, gave a commencement address at American University where he called for a recognition of and an appreciation for the humanity we share even in the midst of stark political differences. He said:

No government or social system is so evil that its people must be considered as lacking in virtue. As Americans, we find communism profoundly repugnant as a negation of personal freedom and dignity. But we can still hail the Russian people for their many achievements – in science and space, in economic and industrial growth, in culture and in acts of courage …

So, let us not be blind to our differences – but let us also direct attention to our common interests and to the means by which those differences can be resolved. And if we cannot end now our differences, at least we can help make the world safe for diversity. For, in the final analysis, our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s future. And we are all mortal.

President Kennedy had no qualms about vigorously defending American democracy against the dangers and evils of Soviet communism. But he also never forgot that communists – yes, even communists – are people too.

The tragedy of this past Wednesday is a stark and dark reminder of what happens when we forget that our political adversaries are still our brothers and sisters in humanity. To put it in uniquely theological terms: our political adversaries are still God’s image-bearers. This means a Republican has never met a Democrat who is not made in God’s image. And a Democrat has never met a Republican who is not the same. So may we guard our actions, guard our tongues, and, above all, guard our hearts as we engage those with whom we disagree. After all, our hearts were made not to hate our opponents, but to love them.

Let’s use our hearts as God intended.

A Forgiveness That Kills Death

When Mark Zuckerberg first unveiled Facebook Live, he touted it as a service that allowed people to express themselves in “raw” and “visceral” ways:

Because it’s live, there is no way it can be curated. And because of that it frees people up to be themselves. It’s live; it can’t possibly be perfectly planned out ahead of time. Somewhat counterintuitively, it’s a great medium for sharing raw and visceral content.

This is true. But I’m not sure broadcasting a murder on social media is what Mr. Zuckerberg had in mind. But on Easter Sunday, last weekend, this is exactly what happened.

74-year-old Robert Godwin Sr. was walking home from an Easter meal with his family when he was stopped by Steve Stephens. Before Mr. Godwin knew what was happening, he was dead and Stephens was on the run. The following day, Stephens was spotted in Pennsylvania at a McDonald’s drive-thru. When police took pursuit, Stephens took his own life.

This is a shocking story. But it took an even more shocking turn when Mr. Godwin’s family was interviewed by CNN’s Anderson Cooper. The anchor asked the family what they learned from their father. They answered:

The thing that I would take away the most from my father is he taught us about God, how to fear God, how to love God, and how to forgive. And each one of us forgives the killer, murderer.

Clearly shocked, Mr. Cooper asked, “You do?” To which the family responded:

We want to wrap our arms around him…And I promise you I could not do that if I didn’t know God, if I didn’t know Him as my God and my Savior…It’s just what our parents taught us. It wasn’t that they just taught it, they didn’t just talk it, they lived it. People would do things to us and we would say, “Dad, are you really going to forgive them, really?” and he would say, “Yes, we have to.” My dad would be really proud of us, and he would want this from us.

Mr. Cooper, amazed at this family’s willingness to forgive a man who murdered their father in cold blood, wrapped up the segment by saying:

You talked about how your friends would say they wish they were Godwins. I know a lot of people watching tonight – and certainly I speak for myself – I wish I was a Godwin right now because you all represent your dad very well.

Jesus famously said, “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you” (Matthew 5:44). Anyone who has ever had to face down an enemy has probably found this to be a nice sentiment in theory, but painfully difficult to practice. And yet, Jesus commanded us to live this way because He knew it was the only way to confront sin and destroy it. When someone sins against us and we retaliate, we have only traded injury for injury. But when someone sins against us and we love and forgive them, as the Godwins did, we have taken their sin and, instead of meeting it with something similar, we destroy it with something better.

Easter is a day when we celebrate life. Steve Stephens tried to turn it into a day of death. But death lost when the Godwin family forgave. For where there is forgiveness, there is life. After all, how do you think we receive eternal life? Only through the forgiveness of sins that comes in Christ.

“God has rescued us from the dominion of darkness and brought us into the kingdom of the Son He loves, in whom we have redemption, the forgiveness of sins.” (Colossians 1:13-14)

Honor, Dignity, Victimization, and Power

It doesn’t take much to offend people these days. Sometimes, it doesn’t take anything at all. This is what Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning argue in their paper, “Microaggression and Moral Cultures.”

Campbell and Manning cull their definition of what constitutes a microaggression from Derald Wing Sue, professor of counseling psychology at Columbia University. Microaggressions are:

The brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, and environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial, gender, and sexual orientation, and religious slights and insults to the target person or group.[1]

Two things are especially notable in Wing Sue’s definition. First, microaggressions can be either “intentional or unintentional.” What counts is not what a sender intends, but what a receiver perceives. Second, words like “indignities,” “hostile,” and “derogatory” in Wing Sue’s definition cast microaggressions in a vocabulary of victimization. Microaggressions, no matter how pint-sized they may seem, are really part of a broader caste system that relentlessly oppresses certain groups of people. The cry of those who perceive themselves as having been microaggressed, then, is really the cry of those who have been systemically victimized by this system and its cultural and socioeconomic assumptions.

Interestingly, Campbell and Manning argue that, for all the complaining that the microaggressed may do about being victimized, our newfound concern with microaggressions actually encourages a culture of victimization rather than discouraging it:

Victimization [is] a way of attracting sympathy, so rather than emphasize their strength or inner worth, the aggrieved emphasize their oppression and social marginalization … We might call this moral culture a culture of victimhood because the moral status of the victim … has risen to new heights.

In an article for the Atlantic, Conor Friedersdorf cites one example of a blossoming culture of victimization in an exchange between two students at Oberlin College. In the exchange, a white student invites a Hispanic student to a game of fútbol who takes offense at the invitation, writing on an Oberlin blog devoted to calling out microaggressions:

Who said it was ok for you to say futbol? … White students appropriating the Spanish language, dropping it in when convenient, never ok. Keep my heritage language out your mouth![2]

A big blow up and a public shaming over a single word. Welcome to the world of microaggressions.

Of course, things were not always this way. Before there was a culture of victimization, Campbell and Manning point out that there was a culture or honor. In this culture:

One must respond aggressively to insults, aggressions, and challenges or lose honor. Not to fight back is itself a kind of moral failing … Because insulting others helps establish one’s reputation for bravery, honorable people are verbally aggressive and quick to insult others.

After a culture of honor came a culture of dignity, where:

People are said to have dignity, a kind of inherent worth that cannot be alienated by others … Insults might provoke offense, but they no longer have the same importance as a way of establishing or destroying a reputation for bravery. It is commendable to have a “thick skin” that allows one to shrug off slights and even serious insults.

Though vestiges of these cultures of honor and dignity remain (compare Campbell and Manning’s definition of a culture of honor with some of the things Donald Trump has said in his presidential campaign and you’ll quickly realize that even though honor culture is on the decline, it is certainly not dead), they are quickly losing ground to a culture of victimization.

But why?

The answer seems to be “power.” Victimization, in our culture, can often be the fastest track to status and power, just as, in previous ages, honor and dignity were inroads to influence. For instance, in recent clashes over same-sex marriage, many in favor of the institution claim discrimination and victimization while many against same-sex marriage claim discrimination and victimization as well. Both groups hope that, by portraying themselves as aggrieved, oppressed, and victimized, they can engender sympathy and, ultimately, the upper hand in this debate. In other words, both sides are hoping to gain cultural capital, or power, by means of their own victimization.

Certainly, not all instances – indeed, not even most instances – of victimization represent grabs for power. One thinks of those who are sexually assaulted or emotionally abused. Such tragic examples of victimization have nothing to do with power. Rather, they represent grave injustices and deserve our prayers, our sympathy, and our action. But in cases of microaggressions and similar self-declared cries of victimization, for all their claims of powerlessness, they often turn out to be nothing more than cynical means of leveraging power.

It is here that we find that, for all of their differences, the cultural systems of honor, dignity, and victimization hold something in common: they are all means to an end of power. And this is where all of these systems run into trouble.

In His ministry, Jesus sometimes fought for honor, sometimes upheld human dignity, and sometimes embraced victimization. But His goal was not that of gaining power. When Jesus fought for honor, it was the honor of God Himself for which Jesus fought, refusing to allow the religious elites of His day to honor God with their lips while blaspheming Him in their hearts (cf. Matthew 15:8). When Jesus upheld dignity, it was the dignity of the ridiculed and marginalized He championed, like the time He rescued a woman caught in adultery from being stoned (cf. John 8:2-11). And when Jesus allowed Himself to be victimized on a cross, He did so not as a backdoor to power, but in order to ransom us from our sin (cf. Mark 10:45). Jesus, it turns out, picked up on elements from each of these cultures without endorsing the shared goal of all of these cultures. He used honor, dignity, and victimization as ways to love people rather than dominate them.

Like Jesus, His followers should feel free to fight for honor, uphold human dignity, and even see themselves, in some instances, as victimized. But none of these cultural constructs, in the economy of Christ, should be methodically used as mere means to power. Rather, they are to be used to love others.

So for whose honor will you fight? And whose dignity will you champion? And how can your victimization lead to someone else’s restoration? Rather than eschewing these cultural constructs altogether, let’s use them differently. Let’s use them for love. For when we use these things for love, even if we do not gain power culturally, we exercise power spiritually. And that’s a better kind of power anyway.

__________________________________________

[1] Bradley Campbell & Jason Manning, “Microaggression and Moral Cultures,” Comparative Psychology 13 (2014): 692-726.

[2] Conor Friedersdorf, “The Rise of Victimhood Culture,” The Atlantic (9.11.2015).

A County Clerk, Gay Marriage, and What’s Right

It’s not often a small town county clerk becomes a household name. But Kim Davis has managed to pull of just such a feat after going to jail last week for refusing to issue marriage licenses from her office. The Washington Post reports:

The Kentucky clerk drew headlines for refusing to issue marriage licenses to all couples, gay and straight, after the Supreme Court ruled earlier this summer that same-sex couples have the right to marry. An Apostolic Christian, Davis has said it would violate her faith to put her name on a marriage license for two people of the same sex.

She was sued by several gay couples and was ordered by [Judge] Bunning to begin issuing the licenses this week. When Davis defied the judge’s order, the couples asked for Davis to be held in contempt and fined.

But Bunning decided to jail Davis, saying fines would not be sufficient to compel compliance because Davis’s supporters could raise money on her behalf.

“The idea of natural law superseding this court’s authority would be a dangerous precedent indeed,” Bunning said.[1]

Not surprisingly, demonstrators, both in support and in protest of Mrs. Davis, gathered outside the courthouse where she was sentenced:

Ashley Hogue, a secretary from Ashland, held a sign outside the courthouse that read, “Kim Davis does not speak for my religious beliefs.”

“This is so ugly,” she said, wiping away tears. “I was unprepared for all the hate.”

Demonstrator Charles Ramey, a retired steelworker, downplayed the vitriol.

“We don’t hate these people,” he said, holding a sign that read, “Give God his rights.” “We wouldn’t tell them how to get saved if we hated them.”[2]

On the one hand, I am somewhat puzzled why Mrs. Davis, if she could not in good conscience carry out one of the duties for which state taxpayers are compensating her, did not simply resign her position. After all, for Mrs. Davis to refuse to issue marriage licenses not only to same-sex couples, but to all couples, and to make it incumbent on the clerks who work for her to follow suit hardly seems the best way to handle a personal religious objection, as Ryan T. Anderson, a senior research fellow at the Heritage Foundation, makes clear in this thoughtful article. Mrs. Davis explains her reasoning in the USA Today article: “‘If I left, resigned or chose to retire, I would have no voice for God’s word,’ calling herself a vessel that the Lord has chosen for this time and place.” Her explanation begs the question: would she really have no voice for God’s Word if she was not a county clerk? Couldn’t she be a witness for Christ in ways that involve less emotional, political, and rhetorical volatility than refusing to issue marriage licenses? And what does she do when she has to perform other duties that could – and perhaps should – violate her conscience, such as legally licensing divorces for couples who are not splitting for biblically appropriate reasons? I’m not sure I completely understand Mrs. Davis’ thinking.

On the other hand, I am also not unsympathetic to her plight. Here is a government worker who was thrown in jail because she, in her vocation, was seeking in some way to abide by what God’s Word says about sexual boundaries. A Christian theology of work says that no matter what we do, we ought to view ourselves as “working for the Lord, not for men” (Colossians 3:23). Mrs. Davis seems to be trying to put this theological truism into everyday practice. I should also note that she does not appear to have arrived at her practice of refusing to issue marriage licenses lightly. Her conversion to Christianity came on the heels of a history littered by broken marriages and broken hearts. Since her conversion, however, she has maintained a strong stance on biblically informed sexual standards.

This is one of those theologically, ethically, legally, and relationally thorny situations that seems to be increasingly common in our day and age. As Christians, how do we respond? Is Kim Davis right? Or should she resign if she cannot, in good conscience, issue marriage licenses?

In the book of Daniel, we meet a man who, like this county clerk, held a government job. Indeed, he held a very prominent government job. Under the reign of the Persian king Darius, this man Daniel “so distinguished himself among the administrators and the satraps by his exceptional qualities that the king planned to set him over the whole kingdom” (Daniel 6:3). Daniel’s upward mobility, it seems, was virtually limitless until, one day, as he went about carrying out his duties, the laws of the land changed in a way that violated his conscience:

The administrators and the satraps went as a group to the king and said: “O King Darius, live forever! The royal administrators, prefects, satraps, advisers and governors have all agreed that the king should issue an edict and enforce the decree that anyone who prays to any god or man during the next thirty days, except to you, O king, shall be thrown into the lions’ den. Now, O king, issue the decree and put it in writing so that it cannot be altered – in accordance with the laws of the Medes and Persians, which cannot be repealed.” So King Darius put the decree in writing. (Daniel 6:6-9)

As a worshiper of the God of Israel, Daniel could not, in good conscience, follow the king’s edict to pray only to the king – even though he was serving the king as a public official. So what does Daniel do?

Now when Daniel learned that the decree had been published, he went home to his upstairs room where the windows opened toward Jerusalem. Three times a day he got down on his knees and prayed, giving thanks to his God, just as he had done before. (Daniel 6:10)

I have sometimes wondered why Daniel didn’t try to negotiate some sort of compromise. Couldn’t he have stayed downstairs in a private room to pray to the true God rather than going upstairs and kneeling before an open window so everyone below would know exactly what he was doing? Couldn’t he have simply put off praying altogether in order to comply with the edict without committing idolatry against his God? After all, the edict was only in place for thirty days. In this instance, Daniel, according to his conscience, could do neither. He had to live out his faith, even if his faith was in conflict with his vocation as a public official and his status as a citizen of Persia.

You probably know the rest of the story. Daniel’s sentence was not just a jail cell, but a lions’ den. Daniel was willing to go to his death for his confession of faith. But, miraculously, “God sent His angel, and he shut the mouths of the lions” (Daniel 6:22).

It’s not difficult to draw parallels between Daniel’s story and Mrs. Davis’ story, save that we do not yet know how Mrs. Davis’ story will end. For us who are looking on, there are a couple of lessons I think we can take away from Daniel’s story. First, Daniel’s refusal to obey Darius’ edict had nothing to do with a political victory and everything to do with theological fidelity. I fear that, all too often, we can prioritize the politics of an issue like gay marriage specifically over a biblical theology of what marriage is generally. Any stand that we make must never be simply for the sake of winning a political battle, but for the sake of staying true to God’s Word. If people perceive that our theology is being leveraged merely as a means to political power, they have every right to be cynical of us and even angry at us. I’m fine if people, as I’m sure they did when Daniel was willing to be thrown to the lions, question our sanity, but we must never give people a reason to question our spiritual sincerity. Second, Daniel served and supported his governing authorities in every way he could until he couldn’t. This couldn’t have been easy for him. The Persians, after all, were pagans who shared none of Daniel’s theological commitments. But rather than fighting them, Daniel supported them in his work. He took a contrarian stand only when it was theologically necessary. I worry that, because of the deep suspicion and animosity that plagues our political system, we have become so devoted to fighting with each other on every front that we have lost our ability to take credible stands on the most important fronts. This is not to say that we can never be engaged in the political process – we do live in a democratic republic, after all – but it is to say that our governing authorities are first and foremost gifts from God to be supported by our prayers rather than political enemies to be bludgeoned by our anger.

As I think about Mrs. Davis’ predicament, I can appreciate her stand. My prayer for her, however, as she remains steadfast in her opposition to a Supreme Court ruling, is that she also proves stalwart in her commitment to love those with whom she disagrees. A strong stand may be good in the face of a morally untenable court decision. And she has decided to take one. But love – even when it’s love for the gay couple that comes walking through the door of the county clerk’s office – is absolutely necessary for Godly, gracious relationships. I hope she’s decided to give that.

______________________________

[1] James Higdon and Sandhya Somashekhar, “Kentucky clerk ordered to jail for refusing to issue gay marriage license,” The Washington Post (9.3.2015).

[2] Mike Wynn and Chris Kenning, “Ky. Clerk’s office will issue marriage licenses Friday – without the clerk,” USA Today (9.3.2015).